Wikipedia defines a cone as a ‘three-dimensional geometric shape that tapers smoothly from a flat base (frequently, though not necessarily, circular) to a point called the apex or vertex.

Famous cones include Hawaii’s Mauna Loa volcano, a Mr Whippy ice cream and the frequently replaced traffic cone atop the Wellington statue in Glasgow. Another one, perhaps somewhat less familiar is Edgar Dale’s Cone of Experience. Dale, a 20th Century American Educator, developed a theory that learning retention is progressively enhanced as more senses activated.

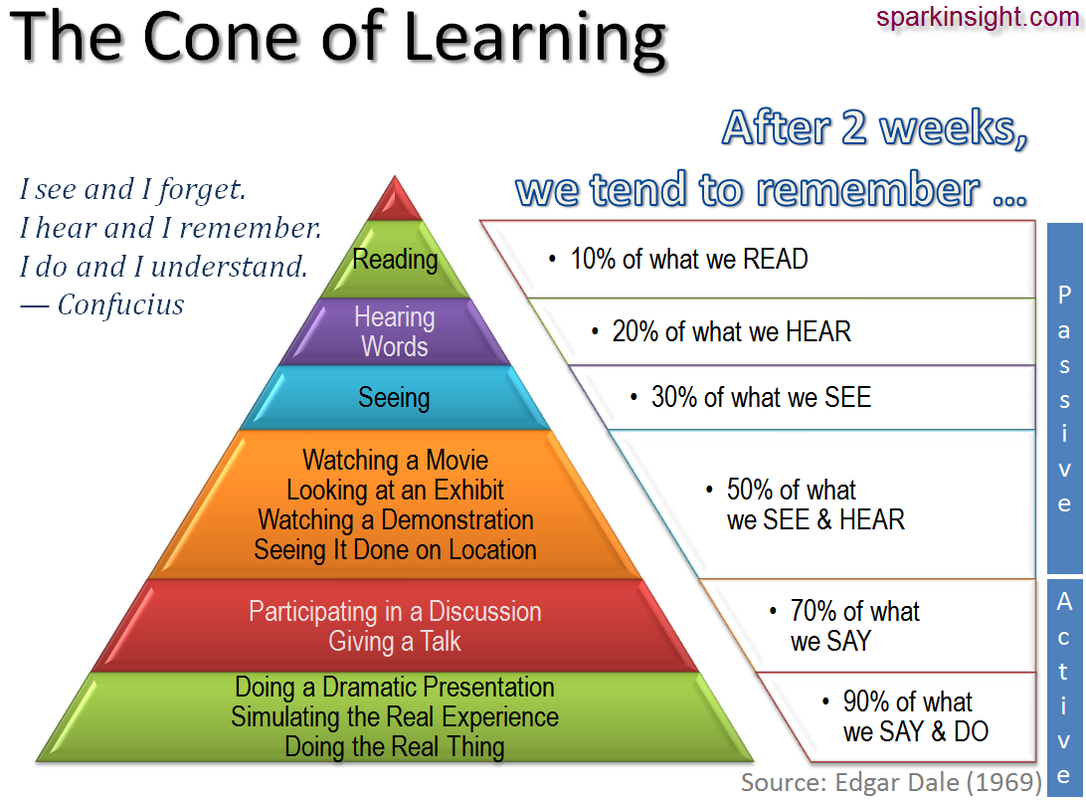

At the top of the cone are reading and hearing, the traditional and enduring ‘talk and chalk’ of 19th century teaching method, where the least amount of what is communicated is retained after a significant period (Dale estimated 10 to 20%). Further down the cone (but up the retention scale) is watching videos or attending exhibits. Dale calls this category Demonstrate, where he postulates that 30 to 50% of information is retained. The most effective means of engendering retention is what I would call the internal feedback approach where students write about what they have learned or, even better, do what they have learned. Dale suggests that almost all salient information is retained in this way (70 to 90%).

My personal journey in Process Safety Training over the past 10 years (started in Dubai – thanks @Andy Gibbins) has gradually segued from cone apex toward its base. My awkward initial sessions were very much more projective than interactive. I’m not even sure I used any videos in those days – very old school (without the chalk). As my confidence and experience grew, I added videos, animations and interactive quizzes stimulating the material and, I now realise, better embedding it.

A few weeks ago, I found myself preparing to start a HAZOP for Savannah Energy in Lagos, Nigeria. HSE coordinator Justin Aliekwue gave a short meeting safety chat, but with a slight twist. As the office layout was a bit unusual, he suggested that, along with the narration of the building egress slide, he could actually show the newbies where to go in the event of an alarm sounding. So I followed him, absorbing the action I would make in the event of an incident. And it made me think that Edgar Dale would have been proud of us, no doubt reflecting from his cloud that should the worst happen, in spite of our panic, we would now be more likely to escape. Justin had allowed us to practice the task in his presence, encouraging us to succeed and only intervening if egregious mistakes were made. He was reactively mentoring.

Towards the end of the HAZOP, I had the opportunity to return the favour. A challenging and potentially hazardous operation was being envisaged, for which a risk review was appropriate. As I had successfully facilitated the HAZOP, I was the obvious candidate to lead it – and it would have stroked my ego if I had done so.. However, just as we were due to start, it occurred to me that it would be more beneficial if I deferred to one of the Savannah Process Engineer involved in the project – @Israel James. In fact, I rather overplayed my hand, by being unable to answer a question Israel asked me during his facilitation as I was distractedly reviewing the HAZOP worksheets. Nevertheless, I am confident that Israel retained significantly more about the mechanics and subtleties of facilitating by doing it in a safe and supportive environment.

In order to drive relentlessly down the cone of experience and provide maximum benefit for the organisation, those wishing to impart their experience should leave their egos at the door, take a deep breath and reactively mentor.